From “Russian Tea-houses and Tea-drinkers” in Chatterbox, 1867

How greatly tea is used in England by every class of society, we all know… But greatly as tea is used in England, it is still in Russia more common. From the palaces of the great and wealthy nobles, down to the wretched hovels of the poor peasants, tea is the universal beverage. – James F. Cobb

James F. Cobb noted the significance of tea in Russian culture in his 1867 article “Russian Tea-houses and Tea-drinkers” for the English publication Chatterbox. While Mr. Cobb noted that British tea culture has its own interesting history and customs, Russian culture is steeped in its own rich tea traditions.

Pictured right: Gilded silver teapot with the Imperial Eagle. St. Petersburg, ca. 1785

Russian tea’s status as a national beverage was slow to brew. When it was first introduced in the seventeenth century, Russians were skeptical. This early tea was very different from the tea drunk today. The tea was in a brick form, which was smashed and mixed with grain and butter, and then consumed as both a meal and beverage.

In the eighteenth century, during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762-1796), tea consumption increased slightly, but it remained expensive and rare, confining its consumption to the Russian aristocracy who used it primarily for medicinal purposes.

It was not until late in the nineteenth century that tea became a national beverage consumed by all classes. By this time, the cost of tea had decreased by half, and thus more widely accessible. Also by this time, Russian tea, and its customs and material culture, became associated with national identity thanks to the work of the country’s most revered writers. Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Checkov wrote about tea as a part of everyday life, celebrating the samovar in particular as a symbol of Russianness.

It was not until late in the nineteenth century that tea became a national beverage consumed by all classes. By this time, the cost of tea had decreased by half, and thus more widely accessible. Also by this time, Russian tea, and its customs and material culture, became associated with national identity thanks to the work of the country’s most revered writers. Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Checkov wrote about tea as a part of everyday life, celebrating the samovar in particular as a symbol of Russianness.

Pictured left: Gilded silver and cloisonné enamel teapot. Moscow, ca. 1900

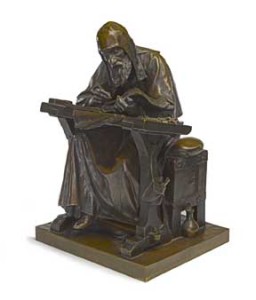

Some scholars speculate that the samovar is actually an English invention, as both the English and Dutch made the earliest vessels for brewing tea and coffee in the late seventeenth century. The first samovar likely came to Russia in the early eighteenth century, taken by Peter the Great as one of many aspects of western culture he hoped to emulate to modernize Russia. The technology of the samovar better suited a Russian home, which was heated with a large stove, instead of an open fireplace to easily boil water. It is not the samovar itself that makes Russian tea. Rather, the samovar dispenses boiled water for diluting the concentrated tea, which is brewed in a small teapot, or zavarka, as shown in the introductory illustration.

Pictured above: antique Russian lacquer tray depicting peasants drinking tea. By the Lukutin Factory, Moscow, 1888-1894.

By the turn-of-the-century, the invented tradition of Russian tea was an integral part of Russian identity. For Russians, the day began and ended with tea. In the morning it was enjoyed with sweet buns, plain rolls, or bread with butter and maybe a little cheese. A few hours after dinner was vecherny tchai, or evening tea consumed with various cold cuts, cheeses, small cakes and candied fruits.

Tea was enjoyed inside and out of the home. In the nineteenth century men congregated in teahouses according to their class, with ones for wealthy merchants and others for their carriage drivers. The gendering of Russian tea culture was delineated by these establishments and also by objects. Men drank their tea from a glass set in an elaborately ornamented metal holder, like the one picture below, while women drank their tea from a cup.

Pictured: Gilded silver and cloisonné enamel tea glass holder. By the 11th Artel, Moscow, ca. 1910.

Regardless of how much Russian tea customs are the product of nineteenth-century nationalism, beautiful works of art, like the tea glass holder and teapots illustrated in this post, attest to the significance of tea in Russian culture, past and present, even if that past is not so long ago.

For all our ALVR Blog posts, please click here.

745 Fifth Avenue, 4th Floor, NYC 10151

1.212.752.1727

Terms of Sale | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

© A La Vieille Russie | Site by 22.