Victorian lozenge-form pendant earrings with old-mine diamonds and dark blue enamel borders, set in gold.

English ca 1870.

Length: 2 1/2 inches

(approx. 10 cts total)

$52,000

Pair of 18k gold and woven hair pendant earrings. These earrings appear in our Victorian hair jewelry video on our videos page.

English, ca. 1870.

Length: 2 1/4 inches

$2,700

This item is available for purchase in the ALVR shop.

These cameo earrings in the Roman Revival style are of hardstone, an indicator of their quality. Gold filigree and granulation border the ladies in profile, further emphasizing cameos as miniature works of art.

The small, low relief sculptures we recognize as cameos date to antiquity, used in Classical Greece and Rome to depict portraits and mythological scenes. There were many cameo revivals over the ages, particularly in the Renaissance and eighteenth-century. In the nineteenth-century, cameos became widely coveted for use in personal adornment.

Napoleon and his first wife Josephine are credited with setting the fashion for nineteenth-century cameo jewelry. Many cameos were brought back to France after the 1786 Italian campaign of the French Revolutionary Wars. Many of these were of Greek or Roman origin. Napoleon soon turned to the medium for cultivating his persona as the new Emperor Augustus, having cameo portraits made of himself in a laureate profile. Josephine also adorned herself in cameo jewelry, most notably a cameo and pearl tiara by Chaumet. The trend became increasingly popular, as the following from the Journal des Dames attests:

“a lady of fashion wears cameos on her belt, cameos in her necklace, a cameo on each of her bracelets, a cameo in her diadem.â€

In the Victorian era, cameos became especially revered as travel souvenirs and wearable sculptures. Many cameo jewelry designs were inspired from sculpture, a highly regarded art form in the Victorian period for use as architectural accents.

Cameos were traditionally made from hardstone. Commonly varieties of agate, such as onyx, sardonyx, and jasper, enabled a cameo carver to create an image in more than one color because of their multiple layers. Cameos were also carved from shell, a light weight material conducive to jewelry making. Such easy manufacture made cameos more accessible to the growing middle class, therefore increasing their popularity.

Beautiful and timeless, cameos are a window to the past and a fitting accessory for the present!

Black diamond and old-mine diamond cluster pendant set in platinum and gold.

English, ca. 1890.

Length: 1 inch (excl. bail)

(Black diamond 37 cts)

Naturalism bloomed in the nineteenth century. Fashionable ladies adorned themselves with elaborate floral jewels like these rose and peony brooches and cornflower hair ornament. The period’s fascination with flora developed into the Victorian language of flowers, which was used to express a range of sentiments. Each of the following jewels has a different meaning and depicts a different stage of blooming, demonstrating the romantic interest in lifecycles:

The rose about to blossom,

Diamond brooch in the form of a rose, set in gold and silver. English, ca. 1860.

Roses have many meanings depending on their color, but primarily express love. For example, tea rose symbolizes love remembered, pink rose represents secret love, and a white rose signifies innocence.

The peony in full bloom,

Tremblant old-mine diamond peony spray brooch mounted in silver and gold. The brooch was possibly made by an English jeweler for the Russian court, circa 1860.

In the language of flowers, peonies symbolize bashfulness, compassion, and happy marriages.

The cornflower, with its cascading, en pempille, petals, on the verge of decay:

Diamond cornflower hair ornament, set en tremblant, and mounted in silver and gold. French, attributed to Oscar Massin, circa 1850.

The en pempille technique, referring to the cascading stones, combined with the springs of the en tremblant setting, enhances the sense of delicacy and refinement the Victorians expressed through cornflowers in their floral language.

Each of these is a unique example of how master craftsman imitated nature in jewelry. Often set en tremblant, floral-themed jewelry sprang to life, with diamonds sparkling like dew drops, creating a playful rendering of nature out of nature’s materials.

Queen Victoria was so enamored of the Scottish landscape that she and Prince Albert purchased a Scottish residence, Balmoral Castle, in 1852. The royal family soon adopted Highland dress in the form of tartans and jewelry. Such jewelry came from the land itself, often called “Scotch pebblesâ€, from the use of native hardstones.

Commonly used stones, often mounted in silver, included bloodstone, carnelian, polished agate and granite, citrine, garnet, pale amethyst, and jasper. Cairngorm, a smoky yellow quartz, from the Cairngorm Mountains, was the most favored stone.

Brooches were among the most popular forms of Scottish jewelry. The Scottish dirk, or dagger, was a recurring design motif, evidenced by our sgian dubh brooch, covered in a previous blog post. Other common designs included the Saint Andrew’s cross, butterflies, anchors, and love knots.

Circles were also common, like our agate, bloodstone, and citrine open ring, or penannular, stick pin (pictured above). Â Our stickpin is an abstraction of the generic Scottish-ring brooch, which usually featured a pinhead in the form of a thistle. Such brooches are inspired from the penannular brooches with thistle-headed pins of the Viking period (793-1066) found in Ireland and Scotland, and were used to fasten garments.

In the Victorian age, Scottish jewelry was often worn with tartan costumes for ice skating. In our own age, they are suited for everyday wear, no matter your intended activity (or lack of plaid).

In traditional Scottish highland dress a knife called a sgian dubh, (prounounced skeen doo), is worn in a sock. Pictured above, a sgian dubh handle has been cleverly repurposed into a beautiful brooch.

In Gaelic sgian means knife or dagger, and dubh means black. In this context, black is thought to mean hidden, or secret. This conclusion stems from the antecedent of the sgian dubh – the sgian achlais, (pronounced ochles), a larger dagger concealed in a jacket sleeve dating to the 17th and 18th centuries. Upon visiting someone’s home, visitors were expected to reveal their weapons.

Sgian dubh brooches resulted from the Scottish Romantic period in the nineteenth century, a revival movement inspired by the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott and King George IV’s visit to Scotland in 1822. The King’s image in traditional highland garb and a historically-themed pageant helped cement Scottish national identity, uniting all Scots through a distinctive, national dress.

Queen Victoria, too, ever the tastemaker of her day, greatly contributed to Scottish romanticism, with ornamental sgian dubhs and other Scottish daggers peaking during her period of rule.

Gifts of jewelry as tokens of affection date from ancient times, featuring design trends like cupid, clasped hands, lover’s knots, mottoes, and hearts.

The heart symbol has been a consistent representation of love. Mythologists surmise it evolved from the ivy leaf, an ancient symbol of immortality. It was a common wedding gift in ancient Greece, and came to represent friendship and fidelity due to its snuggling and nestling characteristics and year-round greenness.

Certain historical symbols of love seem quite strange to modern eyes. For example, the use of hair in sentimental jewelry was quite popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Hair was woven into jewelry, or hidden in lockets and underneath portrait miniatures of loved ones.

Some pieces of nineteenth-century jewelry contained messages through the ‘language of stones,’ where stones were arranged so that the first letter of each one revealed a hidden message. A later example of the mystery in sentimental pieces is our Naval Signal Flag Bracelet, spelling out “ I Love You.†In case that wasn’t cute enough, the gold links are kissing seahorses, another symbol of commitment as they mate for life.

These symbols of love have stood the test of time, just like antique jewelry. Our collection includes hearts, bows (if you are about to “tie the knotâ€), or you might choose something unconventional to imply your own hidden message. Whichever you choose, it will be timeless; after all, diamonds are not the only things that last forever.

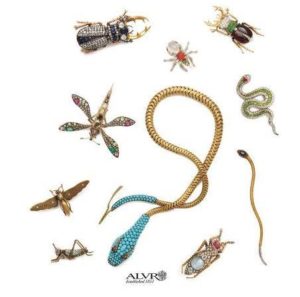

The rapid industrialization of the nineteenth-century contributed to an ever expanding world, a bigger world now open for study. Increased interest in science, particularly natural history, brought pieces of this world into people’s homes and on their person.

Ferns and terrariums became common in parlors, as were aquariums, taxidermy, and shell collections. This penchant for collecting naturalia goes back to the curiosity cabinets of the Renaissance, but it was the Romantic movement at the end of the eighteenth century that paved the way for everyone to become a bit of a naturalist in the Victorian period. Natural specimens were not only found in personal parlors, but for public viewing in the many natural history museums opening.

It was only natural people began wearable collections. Our exhibition certainly attests to the profusion of insect jewelry in this period, encouraged by the rise of entymology in the middle of the nineteenth-century.

It was only natural people began wearable collections. Our exhibition certainly attests to the profusion of insect jewelry in this period, encouraged by the rise of entymology in the middle of the nineteenth-century.

Darwin, too, and his theory of evolution certainly encouraged interest in the natural world, altering man’s relationship with flora and fauna. One wonders what Darwin thought of the bejeweled critters worn in his own time, and now, clearly survivors of the fittest, on display in our exhibition. Also on view are Fabergé animals and fine art, including drawings by Alexandre Iacovleff. Stay tuned the next few weeks for more background information on these exhibition highlights.

We invite you now to become a naturalist – come into our parlor for a look at these bejeweled specimens of natural selection.

At the turn of the twentieth century, objects relating to fishing, golfing, riding, and hunting became popular jewelry design motifs. Sporting jewelry appealed to men and women alike. The dapper gentleman had a plethora of tiepins and cufflinks to choose from of this kind, likely admiring the riding and hunting references to English country life. The New Woman, too, adorned herself with sporting jewelry, emblems to the athletic lifestyle among her latest freedoms in breaking from the domestic realm, long thought her rightful place.

Fox-hunting was a particularly popular sport for the fashionable Englishman in this period, as only the fox remained of all the animals that could still be chased on horseback. The ability to hunt on horseback signified high status, as only the wealthy had such leisure time and could afford to care for horses and acquire the proper accoutrements.

Much sporting jewelry featured reverse crystal designs, a jewelry making technique involving long and laborious handiwork. First, the cabochon form is cut and ground by hand. A draft in watercolor is made on the reverse, followed by scratching, and then engraving, the image into the crystal, before painting. The three dimensional effect created by this technique really brings the pieces to life.

These charming pieces equally suit the sportsman of today, or the collector ever in search of history, who will appreciate these miniature pastoral scenes, the end of an era frozen in time.

Utilitarian and decorative, cufflinks have an interesting background. For much of history men’s shirt cuffs were hidden beneath outer garments, as their exposure was considered indecent. This began to change in the sixteenth-century when ruffles, the antecedent to the modern cuff, appeared on men’s dress. In the following centuries men began to adorn their wristbands with buttons, but it was the starched cuffs of the mid-nineteenth-century that necessitated an easier fastening solution, heralding the era of the cufflink. In fact, shirts with attached buttons were fairly uncommon, ensuring the widespread use of this accessory.

Common among the middle and upper classes from this point onward, cufflinks were a welcome addition to the Victorian gentleman’s rather limited repertoire for sartorial expression. A range of whimsy in cufflink designs allowed a man to show a bit of his personality through common themes like playing cards and sports.

In the mid-nineteenth-century guide The Gentleman’s Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness, author Cecil B. Hartley makes the following recommendation concerning jewelry:

“Let it be distinguished rather by its curiosity than its brilliance. An antique or bit of old jewelry possesses more interest, particularly if you are able to tell its history, than the most splendid production of the goldsmith’s shop.â€

Antique cufflinks provide the gentleman of today with both curiosity and brilliance to enhance his wardrobe, and perhaps, more importantly, a story on his sleeve.

Remnants of the golden dream, these buckles of California gold commemorate the state officially joining the Union in 1850. The design includes imagery from the California coat of arms. On the left, the goddess Minerva sits with a grizzly bear at her feet, referencing how California, too, came fully formed, having no territorial probation.

In an 1854 history of the state, one author notes how “the plain traveller [sic] from the east will notice the profusion of rich jewelry worn here by every class, and by both sexes.†Naturally, the adventurers headed west to seek their fortunes included jewelers. Through the jewelry companies they formed they aspired to deflect attention from the jewelry centers of the east and provide the entire Pacific coast with jewelry from San Francisco.

It was not uncommon for the forty-niners to send relics of their labor to loved ones left behind. Those with the tools and time fashioned nuggets into rings, crosses, and other pieces of adornment. Others sent small amounts of gold for family members to have made into wearable relics by their local jeweler.

An assortment of jewelry also catered to tourists encouraged to take away natural specimens as souvenirs. California jewelers met the demand with a variety of trinkets including combs, brooches, and rings, which became quite popular in the early 1850s. Much of these mementos proudly displayed clusters of nuggets and incorporated gold quartz into the design. These buckles are a bit unusual in their apparent break from tradition. Collectors are sure to be struck by their historic and aesthetic value, ready to exclaim, ‘eureka!’

745 Fifth Avenue, 4th Floor, NYC 10151

1.212.752.1727

Terms of Sale | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

© A La Vieille Russie | Site by 22.